V ( Dubashi Lifestyles : image as Reality )

To appreciate fully the extent to which the constructed identity became internalized in the self-perception of the rich dubashes themselves, we need to reconstruct their lifestyles in the 18th and 19th centuries. The diaries of Ananda Ranga Pillai 42 provide much information which make this reconstruction possible for the mid-18th century. If this is compared with the information for Madras in the early 19th century we get a better picture of the dynamics of social change over half a century. Of particular interest is the changing nature of the interface between the social elite and Europeans over these decades.

(Ananda Ranga Pillai his Family & Pondicherry Society)

Though Ananda Ranga Pillai was extremely reticent about his personal life in his diary which was clearly meant to be a record of his public persona, the few glimpses he provides into his family matters reveal clearly that all important family occasions were celebrated on a lavish scale with great ceremony. The wedding of his eldest daughter Pappal in 1747 was a much talked about event, and Ananda Ranga Pillai was particularly gratified by the compliments he received from the governor Dupleix, who told him, ” All the Europeans, both young and old, think the decorations of the pandal and marriage processions are extraordinarily magnificent”, while the other French officials observed that it was grander than royal wedding. 43 Several years later, in 1755, even when his fortune had begun to decline, the marriages of his two other daughters and his niece were also celebrated in an elaborate style, though he felt that his older daughter’s wedding had been on hundred times finer. Anand Ranga Pillai gave the governor a diamond ring worth 500 pagodas as a gift, the second M.Barthelemy a ring worth 100 pagodas and silks to the other French guests. 44

The custom of lavish weddings continued into the next generation, and the marriage of Muttu Vijaya Tiruvengadam Pillai, the son of Ananda Ranga Pillai’s nephew and successor, Trivenkadam Pillai, in 1791 was also a very grand affair. It was celebrated over four days with processions each night, accompanied by elephants, with torches, fireworks, music and drums which were watched even by the Governor and his wife from terrace of the government. On the last day, an expensive dinner dance for the governor and all French officials was hosted by the father of the groom. 45

Birth, birthday and funerals were also grand public occasions. Ananda Ranga Pillai himself has recorded the great celebrations which marked the birth of his son in 1748. 46 The poet Madurakavirayar was evidently part of Ananda Ranga Pillai’s entourage and was present on all special occasions – like the first birthday of Ananda Raga Pillai’s son , the wedding of his nephew, Tiruvengadam pillai, and the birth of a daughter to Tiruvengdam Pillai – which he commemorated in poems, all with extensive praise of Ananda Ranga Pillai’s qualities, both real and imagined. 47

Funerals were no less markers of social standing, and Ananda Ranga Pillai describes in moving details the funeral of his beloved wife. Mangathayi Ammal in 1756, the procession which passed on roads sprinkled with turmeric, saffron and frankincense, and the funeral pyre of sandalwood. 48 Three days later, with equal gratification, he noted that he, his son and nephew were all offered condolence at the government by the governor, honored with expensive gifts and gun salute. The funeral concluded with a nautch at the diarist’s house to which everybody was invited. 49 Through these elaborate and ostentations public displays the social status of Ananda Ranga Pillai’s family was validated at two levels – first, the awe and wonderment of the local people and leaders of society: second, the appreciation of the Europeans and the official recognition and honors offered by the governor himself.

( Scenario in Madras – A Early 19th Century )

In Madras, by the early 19th century, the colonial state had phased out the dubashes from their many functions, both as personal agents of company officials and as official interpreters, 50 which also undercut the traditional power base of the dubashes. This class now created a new social world in which the English played only a minimal role, reconstructing in the process a self-image which was even more exaggerated than the heroic identity constructed by their poet clients. In this new world the dubashi class no longer looked to the European masters for validating their claims to social leadership, as was the case with the family of Anand Ranga Pillai in Pondicherry. On the other hand, their social status was built on a foundation of an extensive patron-client network within indigenous society.

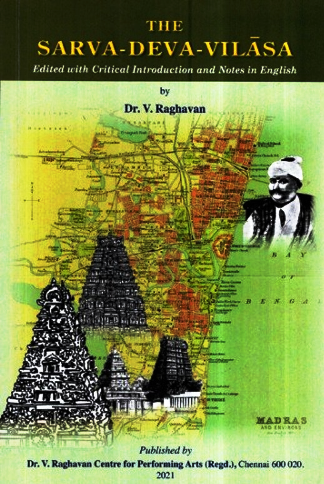

An important, and perhaps only, source of information on Madras society in the early decades of the 19th century from the point of view of local people is the anonymous Sanskrit work, Sarvadevavilasa. 51 The narrative develops as a series of dialogues between the two protagonist, allegorically named Vivekin (the wise one) and Ativivekin (the very wise one), representing the two faces of men of letters seeking monetary support and patronage – the sycophant and the sceptic. 52 The two poets eke out a perilous living as hangers on of the ‘great lords’ (prabhu) of Madras, whom they assiduously follow and cultivate. Even the title of the work, Sarvadevavilasa, is a metaphor for Madras as the “above of the gods “, the rich men who lived in the town. The great value of the work as a source for social history is that, with the exception of the two protagonists who are fictional, every person mentioned in the book was a historical person. 53

The Savadevavilasa mentions several leading men of affairs of Madras society, including the dubash families of Kovur and Manali, the merchants Kolla Ravanappa and Lingi Chetti, (the respective leaders of the right and left hand castes in the town). Annasami Pillai, the influential ‘dharmakarta’ of the Triplicane temple and many others. But the work is structured around four main patrons – Kalingaraya, a well known resident of Madras, Sriranga, the mirasi dharmakarta of the temple at Tirunirumalai (just south of Madras), Vedachala Mudali of Tottikalai, the son of Kesava Mudali and the dharmakarta of the local temple and Devanayak Mudali, the dharmakarta of the Agastyesvara temple at Nungambakkam in Madras. 54

The poem begins by referring to the four patrons as kings greater than Bhoja (bhojadhikah) “who sat on golden seats inlaid with emeralds, sapphire, rubies, diamonds & other beautiful gems”55 , but soon begins to refer to them as gods who had taken human form and were in this town to protect everyone, omniscient beings who were patrons of learning. 56 The composite image of regal patronage was assiduously cultivated by the rich merchants themselves by their ostentatious lifestyles and public display of power, wealth and virility. The construction of identity was thus an interactive process, fostered by the clients and internalized by their patrons in their self-perception.

For instance, when Vedachala Mudali set out from Madras for Tottikalai to conduct the annual festival at the temple, it resembled a royal procession which the entire Black Town turned out to watch. The procession commenced to the sound of drums, and had a lead elephant bearing a standard, followed by Vedachala himself on his elephant, accompanied by armed soldiers. Others in the procession included his personal staff, his brothers, the musicians that he supported and patronized, and his gurus, all on elephants, followed by camels carrying tents and equipment. 57

The fable of royalty is repeated in the narrative again and again. Vedachala’s empire (samrajyan) was greater than that of Indra, and Tottikalai, his mirasi village, was his ‘capital’. His personal staff are referred to as minister, (amtya), commander-in-chief (senapati) – perhaps a personal bodyguard – and the keeper of treasury (kosadhikar) – probably the accountant. The rich men themselves also reinforced this image. Each one of them is said to have had his personal ‘army’ – or armed retainers. They had distinctive, individual standards and tents in their own colors. 58.

The two poets frequent the locals where the patrons would be found. They thus go to the garden estates of Kalilngaraya and Sriranga, (probably near Triplicane), where they meet the great men and present compositions praising them and in return are rewarded on a grand scale. Temple festivals were the other major venues where all the great men could be found. With the exception of Kalingaraya, the other three were all dharmakartas of temples in and near Madras. It is clear that being in control of temples was an important determinant of social standing which was further reinforced by the grandeur with which they celebrated temple festivals, displaying their wealth.

Temple festivals thus became occasions which subserved several objectives. They re-established the bond between the general public and the patron/dharmakartas, since the celebration of temple rituals as prescribed with due solemnity and on as grand a scale as possible was a source of deep satisfaction to the people who identified themselves with the temple in a very personal and fundamental way. Festivals also provided the opportunity for cementing social relations among the rich patrons themselves, when the later visited each other, each riding on an elephant accompanied by a large retinue, so that there could be a grand, public display of their wealth. The host entertained his guests in the most lavish style, which would be reciprocated at festivals in other temples.

Lastly, the hosts organized assemblies (sadas) as a part of the temple festivals where the musicians and other learned men whom they supported could display their talents by giving concerts, holding debates and presenting new literary compositions. 59 These assemblies also offered an opening for poets like the main protagonists who did not enjoy regular patronage to display their creative talents and received some money in return. Raghvan sees in these assembles the network of patronage by which Madras became the centre of classical music and other performing arts in Tamil Nadu. 60

On all public occasions the rich men were accompanied by their mistresses, who were highly talented courtesans. Flaunting these beautiful and accomplished women in public also reinforced the status and image of the rich men. Kalingaraya’s mistress was Narayani, ‘an expert in erotic games’ and a great singer. Sriranga’s mistress was Manga, ” the foremost of the courtesans, very knowledgeable in music and a rich storehouse of erotic art “. Vedachala’s mistress Minakshi was great singer, while Devanayaka’s mistress was so beautiful she was like a divine goddess. 61 The image of the heroic king/lover was by now internalized in the consciousness of the rich men, and one of their favorite public activities was to have a public bath with their mistresses, and sport with them in an open tank or pond (Jalakrida) watched by an admiring public. 62

Like the poets of the earlier era, the two narrators of Sarvadevavilasa also continue to maintain an illusion that their patrons were independent of all superior authority and were sovereign persons in their own right. The presence of the English could not be wished away completely, however, and towards the end of the work, they remark that the English (huna) would have been afraid if they saw the armed soldiers accompanying Kallingaraya. They also ask themselves the rhetorical question, how these maharajas were tolerating the rule of the low-born (foreigners) who were destroying traditional social values and structure (varnasramadharma), 63 The English are referred to as the Huns (huna), or white-faced, (svetamukhah orsitasyah), in obviously derogatory tones. It is not clear whether this represented the view point of a small minority of men of letters who found the traditional world they knew crumbling around them, or it was an attitude shared by many, but the former is probably the more plausible explanation. It is also tempting to infer that these references were essentially inserted to please the egos of the patrons, by fostering the illusion of their omnipotence. The actions of rich men like Annasami Pillai who had publicly challenged the authority of the English Collector of Madras 64 would indicate that the elite class was trying very hard to preserve its own social space free from the authority of the colonial state.

(Conclusion )

It is clear that the changing social relations and equations under the colonial state were predicated as much on an imagined identity constructed both by the English and by indigenous society, as on concrete factors. From the beginning of their settlement in Madras the English had exhibited a deep suspicion of the Indian merchants who could become influential leaders of indigenous society built on their trade with the English Company. What was acceptable in social leadership was the creation of a loyal, subservient class as intermediaries between the colonial state and local society. For the new elite class, leadership meant autonomous authority over the rest of their society, recalling the images of the heroic kings of bygone eras. When the English began to eliminate the official administrative channels through which the new elite could consolidate and validate their social status, they increasingly looked to indigenous institutions and values to achieve their social objectives. Ultimately, however, the English were able to create the kind of social leadership that they envisioned. This was achieved partly by closing out the local rich merchants and dubashes from the public spaces of the colonial state, leaving only such posts as were completely under the control of the English. The introduction of western education, and creating a consciousness of the superiority of European social values and norms over Indian culture and attitudes was perhaps an equally important contributory factor.

Address for correspondence : jmukund2001@yahoo.co.in

( Notes )

[This is the revised version of a part of a larger study titled The View from Below ; Interactions between Indigenous Society and the Early Colonial State of Tamil Nadu 1700 – 1835, (Forthcoming, Orient Longman), funded by a senior fellowship from the Indian Council of Social Science Research. All the material in Tamil and Sanskrit have been translated by me, unless a translated version is specifically indicated ]

- The Indian merchants, by and large, had shown themselves to be eager to trade with the Europeans in other ports like Masulipatnam and Pulicat also. But in the case of Madras and Pondicherry which were new settlement, physical relocation was also involved.

- Despatches from England, January 22, 1692, Para 13 (Public Department, records of Fort St.George, Tamilnadu State Archives (TNSA)

- Despatches from England, April 26, 1721, Para 19-23.

- The English term for accounts keepers ‘kanakkupillai’ in Tamil, Several departments of the Madras government later had the post of “Conicoply” usually filled by Indians.

- Despatches from England, January 8, 1718, page 72

- Susan Nield Basu, ‘The Dubashes of Madras’ Modern Asian Studies 18, No.1, 1984, p 10

- Ibid. p 11

- Public Consultations (PC) September 5, 28 and 29, 1758 (Public Department. Records of Fort St.George TNSA)

- PC December 7, 1781

- PC December 7, 1781

- PC December 31, 1781. The inquiry was finally abandoned for lack of evidence, PC February 7, 1782.

- Sundry Books, Military Department, Records of Fort St.George. TNSA Vol 76 (Charges brought by Nabob Wallajah against the Dubash of J.Hollond, July 9, 1790); Vol 77 (Proceedings of the committee appointed to investigate the charges against Hollond’s administration, July 1, 1791). The brief account which follows is taken from vol 76, pp 1-91 , See also, A.V.Venkatarama Ayyar, ‘Dubash Avadhanum Paupiah and a Famous Trial’, Indian Historical Records Commission. Proceedings, vol xii, Gwalior 1929. Calcutta; 1930 pp 27-36

- Henry Davsion Love, (Vestiges of old Madras 1640-1800) , 3 volumes, London, 1913. vol 2. pp 329-35) reproduces excerpts from Madras Dialogue (1750) in which the Madras dubash, in this case the household servant – commonly referred to as a butler in later years – is depicted as a totally contemptible person, a laughing stock

- Basu. ‘Dubashes’ p 2

- Eugene F Irschick, dialogue and History – Constructing South India, 1795-1895, Delhi, 1994, p 73

- Lionel Place, Report on the Jaghir, July 1, 1799, Board of Revenue Miscellaneous volumes, Chingelput District, vol 45, TNSA. pp 213 – 25. Place’s account was accepted by all official agencies and is now the only version that we have available. So one can only see the dubashes in this phase of history through the eyes of Place. Much of Place’s account was repeated verbatim by Charles S.Crole, Chingleput, late Madras District: A Manual, Madras. 1879, p p 240 – 2

- For a detailed account, see Irschick, ‘ Peasant Survival Strategies and Rehearsals for Rebellion in 18th Century South India, in Temples, Kings and peasants, ed George W Spencer. Madras, 1987, pp 133-68 and Dialogue and History.pp 14-66

- Quoted by Burton Stein, Thomas Manro – the Origins of the Colonial State and his Vision of Empire, Delhi, 1989, pp 37-8

- Proceedings of the Board of Revenue, TNSA, (BORP) December 7, 1795, pp 9342-90

- BORP December 17, 1795 pp 10099-116

- BORP December 21, 1795 pp 10308-56

- BORP November 1, 1798, pp 7821-42

- Chingleput District Records (CDR), TNSA, Vol 447, November 10, 1798 pp 183-5

- BORP April 17, 1797, pp 2230-40

- BORP December 3, 1795, pp 9189-239, in an interesting postscripts to Place’s strictures on Kesava Mudali . a few year later , the BOR recommended to the government of Madras to grant the petition of Kesava Mudali , that he should be allowed three villages, including tottikalai, as ‘shrotriyam’ (on favorable tenure). The BOR commented that this would be in return for his many years of service as a public servant under military storekeepers, and was ‘ the best and most honorable mode of remunerating services and perpetuating the sense entertained by government of fidelity and integrity” (BORP December 28, 1801, pp 15203-4)

- Irschick, Dialogue and History, p 53

- Fifth Report from Select Committee on the Affairs of the East India Company – Madras Presidency, vol ii, London, 1818 (Madras,1883) pp 38-39

- Susan Nield Basu gives an account of Pachiyappa Mudali’s activities using such sources , ‘Dubashes’ pp 16-7; 20

- Tanippadal Tirattu, (Tamil) (An Anthology of Verses), ed by A.Manickam, Part I, Madras, 1984, pp 311-2 (658) {Numbers in parentheses refer to the verse number in the book }

- Ibid, p 313 (661)

- Ibid, P 315-16 (668)

- Ananda Rabga Kovai, (Tamil) (ed) with introduction, by N.Subrahmanian, Madras, 1955. Verse 8 (p 4) and 46 (p 17)

- Ananda Ranga Pillai, The private Diary of Ananda Ranga Pillai, (1736-1761), 12 vols, vols 1 -3 ed by J Frederick Price and K Rangachari, Vol 4 -12 (ed) H Dodwell, Madras, 1904 – 1928 (Reprinted, New Delhi: 1985)Vol 2. p 238 (August 25, 1746), This was the work titled Ananda-ranga.rat-condamu. Another such work was the Ananda-ranga-vijaya-campu. See Raghvan. ‘Notices of Madras’. The Madras Tercentenary Commemoration Volume, London, 1939, pp 108-9.

- Ananda Rangan Kovai. Introduction. pp xxiii

- Pillai, Diary, vol x. Introduction for the details

- One was Durairanga-bhupati, the other, Ananda Ranga Pillai. Tanippadal Tirattu, part 1. pp 313-4 (662); p 316 (667)

- Ibid, p 317-21 (670, 672, 673, 674; p 321 (677), The first four were by Madurakavirayar and the last by Savvadu Pulavar. This person was probably the grandfather of Tottikalai Vedachala Mudaliar of Madras. (see below), and the father of Kesava Mudali, so detested by Lionel Place.

- ‘Kovai’ is a genre of poetry which has romantic/erotic love as its main theme.

- ‘Tanippadal Tirattu’ part 1 , p 321 (676)

- ‘Tanippadal Tirattu’ part 2, Madras, 1998, pp 18-20, (13,14)

- ‘Tanippadal Tirattu’ part 1, pp 421-2 (858, 860)

- This kind of detailed and intimate information is not to be found in diaries of his nephew Tiruvengadam Pillai or his grand nephew Muttu Vijaya Tiruvengadam Pillai which have been published recently in the original Tamil.

- Pillai, Diary, Vol IV, pp110-2 (June 28, 1747), The bride, tragically, died barely a week later on July 7 , Ibid, pp 117-9, ( July 15, 1747)

- Pillai, Diary, Vol ix, pp 316-7 (June 16, 1755)

- Irandam Vira Naykkar Natkurippu, (Tamil) (The Diary of Vira Naykkar the Second), (ed) by M.Gopalakrishnan, Madras, 1992, pp 242-4, (july 8 to 12, 1791)

- Pillai, Diary, vol iv, pp 304-6 (June 7, 1748).

- Ananda Rangan Kovai, ‘Introduction’, pp xxi-xxii

- Pillai, Diary, vol x, pp 61-2 (April 19, 1756)

- Ibid, pp 63-64 (April 2, 1756)

- Basu, ‘Dubashes’ p 18

- Sarvadevavilasa, (Sanskrit), (ed) with critical introduction and notes by V.Raghavan, Madras 1959. Raghavan has not translated the text, but has written a long introduction, in which he gives a brief outline of the work. The references given below refer to the Text, with page number prefixed by T The translation of the text has been done by myself. …………….. { Raghavan (“Introduction”, p 11) dates the work as not earlier than 1979 and not later than 1817. From other internal evidence it is clear that the date is certainly closer to 1820. }

- This is my reading of the two characters. There is an underlying bitterness and irony in Ativivekia’s fulsome praises of rich patrons which is quite unmistakable.

- In the Introduction, (Sarvadevavilasa) Raghavan has traced the identities of not only the patrons (pp21-39), but also of the musicians and courtesans (pp 44-51) mentioned in the work.

- Kalingaraya was one of the “respectable” natives of the Committee set up by the BOR in 1799 to frame the regulations for the functioning of the Triplicane temple. (Madras District Records, TNSA, Vol 1027, November 25, 1799, pp 41-42) ………………………………….. {Sriranga was probably one of the forefathers of the family of M.Bhaktavatsalam, the former chief minister and congress party leader of Madras, whose family are the hereditary dharmakartas of the Trinirlmalai temple. The family records show that one Rangaraja or Sriranga was the dharmakarta of the temple around 1800(Raghavan, ‘Introduction’ pp 30-1)} ……………………………… { Vedachala Mudali have identified as the son of Kesava Mudali(mentioned by Lionel Place) and the grandson of Kalasai Vedachala, mentioned earlier who must have been a contemporary of Ananda Ranga Pillai, supporting my conclusion that the persons mentioned in the Sarvadevavilasa was the grandson} ……………………………………………………………………………………………… {Devanayaka Mudali is mentioned in the BORP in 1820 (June 8, 1820, pp 4046-49) as the dharmakarta of the Agastyesvarara and Vaikunta Permal temples in Nungambakkam. Four years later, the collector Madras writes that Devanayaka Mudali was in financial trouble. He was involved in law suits for debts contracted by him, and “was shut up because of his pecuniary embarrassments” (BORP May 24, 1824, pp 4655-71)}………………………………………………………… {Raghavan traces the family tree and notes that the family had been dubashes in Company service from 1725. (Introduction pp 28-29)}

- Sarvadevavilasa p T 3.

- Ibid. p T 5.

- Ibid. pp T 21-26.

- Ibid. pp T 10, T 22, T 29, T 31, T 53, T 76. Several times Sarvadevavilasa refers to ‘caturanga-sena’ or traditional army with four divisions – infantry, cavalry, chariots and elephants – armed with guns. IT does not seem plausible that the English would have allowed private armies within Madras, but it is possible that the rich men employed armed guards for protection.

- Ibid, pp T 37-38, for the sadas at Tottikalai; pp T 50-1 for the sadas at Nungambakkam; T 65-6 at Tirunirmalai

- Ibid, ‘Introduction’ , pp 44-45

- Ibid, pp T 37-38 ( the bias of the historian is seen in Raghaavan’s censored version of the text in the Introduction, in which he completely omits the details of the sexual relationships between the courtesans and the patrons)

- Ibid pp T 44; T 83-85

- Ibid, pp T 78, T 80

- See Kanakalatha Mukund, ‘The View from Below : interactions between Indigenous Society and the Early Colonial State in Tamil Nadu 1700-18325’, (mimeo, Hyderabad, 2002) for further details of the episode.

Authour Note:-

veejee_06@yahoo.co.in> To:jmukund2001@yahoo.co.in – Fri, 9 Jul at 5:33 pm

Dear Madam, Recently I read one of your article published in the Economic and Political Weekly July5, 2003 “New Social Elites and the Early Colonial State ” (Construction of identity and patronage in Madras) .This artaicle I wanted to publish in my blog ‘ hinduunityblog.wordpress.com’ with your references. Also I am interested to the full list of Dubashes who are all serving under the British. I could able to find around 35 names of such dubash but it seems the list is too long I suppose. There were more than 110 governors served during the British period. Even if you give some reference citation is OK.

with regards ,vedamgopal

jmukund2001@yahoo.co.in> To:gopal vedam – Sat, 10 Jul at 1:48 pm

Dear Sri Gopal Vedam, Thank you for your email. You have intimated that you want to publish my article in your blog and have asked for some additional information. I would like to clarify a few points with regard to this.

- The article was published in the Economic and Political Weekly and as such you need to take their permission for republishing the article.

- I do not have any further information on the names of the various persons who served as dubashes during the 18thand early 19th centuries. In any case, because of advancing age I have discontinued my academic work. You could follow up from the references given in the paper.

- At a personal level, I am very uncomfortable with terms like “Hindu unity” and am opposed to the notion of a “Hindu Bharat Varsha”. My paper was published in a reputed research journal and as such it is in the public domain. I have no control over how it is used by persons who read this paper or the context in which they would want to use it. I would however be very unhappy if my research work is used to promote a narrow ideological agenda based on caste or religious identities. (KanakalathaMukund)

Yours sincerely, Kanakalatha Mukund

veejee_06@yahoo.co.in> To:J. Mukund, Sun, 11 Jul at 11:27 pm

Dear Madam, Thank you very much for your prompt reply. I will write to the economic weekly for permission. Since you said that your views on Hindu unity, bharat varsha are personal & I have no comments except the word uncomfortable, at the same time Hindus are uncomfortable due to the fear of vote bank caste / religious politics & attack of abrahamic faith-that Hindus identity will vanish within a few generation.

My mamaskaram to you & thank once again, Vedamgopal

veejee_06@yahoo.co.in> To:edit@epw.in , Sat, 17 Jul at 12:53 pm

Recently I read one of your article published in the Economic and Political Weekly July5, 2003 “New Social Elites and the Early Colonial State ” (Construction of identity and patronage in Madras) .This article I wanted to publish in my blog ‘ hinduunityblog.wordpress.com‘ with your references. Also note that I have written a letter to the author Kanakalatha for permission & she directed to you, hope to get a favourable response and thanks.

Vedamgopal

nutan@epw.in> To:veejee_06@yahoo.co.in , Mon, 19 Jul at 3:40 pm

Dear Dr Vedamgopal, The copyright of all the articles published in EPW remains with the authors. Therefore, If the author of the paper Dr Kanakalatha Mukund given her permission for the article titled “New Social Elites and the Early Colonial State Construction of Identity and Patronage in Madras” published in our issue of July 5, 2003, we have no problem. You can go ahead. The only thing we request you is that to give proper acknowledgement of the original place of publication of this article with full reference and details, which you have already mentioned that you would do. Please send us a soft copy of her consent for our records.

With best wishes,

Nutan Patel

Editorial Secretary

Economic and Political Weekly

veejee_06@yahoo.co.in> To:jmukund2001@yahoo.co.in ,Mon, 19 Jul at 11:15 pm

Dear madam, I am forwarding the reply letter from EPW & they want your consent letter now hence I humbly request you to sent the same ignoring my blog purpose which you said not comfortable to you. I will not make a tinge of change in the article & if you want I will mention the points which you said under your name.

Hope to get a positive response and thanking you, Vedamgopal

mukund2001@yahoo.co.in> To:veejee_06@yahoo.co.in, Tue, 20 Jul at 9:16 am

Dear Sri VedamGopal, I have no objection to your publishing my article “New Social Elites…”. It should be published with all notes and references exactly as in the original. There should be no editorial comments inserted in the paper.I would also like you to include a copy of my original letter so that my position is made clear to the reader.

Yours Sincerely ,Kanakalatha Mukund

veejee_06@yahoo.co.in> To:J. Mukund,edit@epw.in , Tue, 20 Jul at 9:39 pm

Dear Madam, Thank you very much for your permission and I will follow the instructions you have stated in your letter. Also before publishing in my blog I will send you a draft copy to you.

with regards,vedamgopal

Nutan Patel

Editorial Secretary

Economic and Political Weekly

Dear Sir, Pl treat this letter copy for your reference and thanking you/vedamgopal