( when the Europeans began to trade in India, their commerce was completely dependents on the services of the Indian mercantile class who served as the conduits to the primary producers and local markets. This relationship did not change materially after the Europeans enclaves of Madras and Pondicherry were established. It was, however, redefined, since the indigenous merchants in these early colonial port cities were, at least formally, subservient to the authority of the Europeans. As the same time, the growing importance of the local merchants in these commercial centers created an opening and a space for them in indigenous society through which they could create a new identity for themselves as the new social elite and patrons of local institutions, arts and culture. )

( KANAKALATHA MUKUND )

( Published in Economic and Political Weekly , July 5, 2003 )

( Authors permission letter and her views at the end of the article )

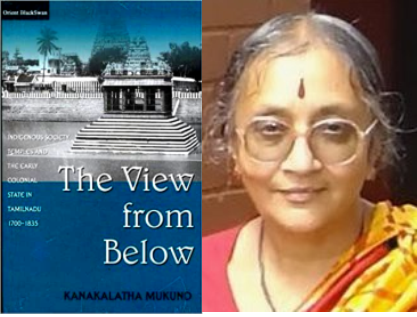

This is the revised version of part of a larger study titled “The view from below” interaction between indigenous society, temples and the early colonial state in Tamilnadu (1700-1835)

1. Background

Between their Europeans masters and the Indian merchants there evolved a curious, ambivalent and symbiotic relationship of mutual dependence and advantage, of manipulation and exploitation. Even after they had acquired their small enclaves on the Coromandel coast, the Europeans continued to need intermediaries who were not merely proficient in the local languages, but were also conversant with local economic conditions, current political realities and the ruling classes. For their part, the merchants seized on the commercial opportunities offered by the new settlements and moved there to trade and prosper.1 In Madras the most influential of these merchants became the chief suppliers of textiles to English Company, known as their Chief merchants, while they were also the personal agents of the English factors. There was no clear separation of the public and private spheres of trade either in the case of the English or of the Indian merchants. Both parties were eager to take advantage of the name of the English East India company to advance their own interests. Yet, paradoxically, the English regarded their Indian merchants with deep suspicion, convinced that the merchants were cheating them in various ways, while also gaining an undue and undesirable influence in local society.

Complaints and accusations by the local English factors at Madras against the merchants were almost as old as the settlement itself. The relations of the English with local merchants had a public and private face. Publicly, the English displayed a paranoid distrust of any merchant who had an independent power base of his own, and lived in a style which was considered unbecoming and ostentatious.

If this was the public face of English attitudes to Indian merchants, the private relations between them was on a different plane altogether. From the beginning the English, who complained that the local merchants cheated them, had a few qualms about extorting money from the same merchants, especially for allowing them to join the Company’s textile trade. This practice became so notorious over the years, that several letters from the Court of Directors of the East India Company expressed strong disapproval of this practice. In 1692 they wrote that it was their absolute order that nothing was to be exacted from the natives upon any pretence what so ever except for the Company’s use.2 This, however, did not stop the practice. The governors, deputy governors and other Company servants continued their extortionate demands, assisted by their personal agents, more commonly referred to as “dubashes”. These demands became so exorbitant that again in 1721 the Court of Directors wrote an exceedingly stem letter to the Fort St.George Council, which was clearly disinclined to take any action, to inquire into the complaints, since the merchants were leaving Madras because of such iniquitous demands.3

Though the involvement of governors in these activities was well known, ultimately, the dubash was the person considered unreliable and treacherous, and the Court of Directors warned the Fort St.George Council to keep “a watchful eye and carry a strict hand over those black fellows, the dubashes and conicoplies,4 .. they are generally the tools made use of by Europeans to oppress the poor natives within our precincts and from thence are taught to squeeze for their own private advantage and to make use of their masters name to prevent the poor sufferers complaining which is an evil so pernicious that we earnestly recommend to every one of you to punish it in every the least appearance.5

There was a significant shift in the employment of private business agents by the English as Madras grew. In the early years, the chief merchants acted on behalf of the English, especially the most senior Company servants, in their private trade also. Generally this practice appears to have faded out, so that the private agents (generally referred to as dubashes) were not usually concerned directly in the Company’s textile contracts. This meant that a distinct and parallel class of influential merchants was beginning to emerge in Madras.

As the settlement of Madras grew in size and trade, it attracted merchants from many diverse castes. In the 1650s almost all the important merchants of Madras were ‘Balijas’ ( ‘ Kavarai’ in Tamil ) or ‘Beri Chettis’. The only merchants from a non-trading caste were the Brahmin brothers who were chief merchants and agents of president Baker. Later migrants to Madras included ‘Komati Chetti ” (vaisya) among the trading caste, while many were from the traditional agricultural castes also. Till the first half of the 18th century, many dubashes came from the traditional merchant castes and families. Susan Nield Basu has observed that in the 18th century Madras it was rare to find, among the more prominent dubashes, a person with a caste title of Chetti or Naik which would indicate a mercantile or martial caste affilication.6 This, however, was a gradual social transformation that occurred later in the 18th century. The agricultural caste seem to have had a special aptitude for working as dubashes, and most of the well known dubashes were ‘Mudaliors’ (Vellalar). Basu has identified that most of the late 18th century dubashes were vellalar from near Madras, Telugu Brahmins, Kanakkupillais (accountants) and Yadavas (shepherds or idaiyar) 7

II ( Madras Dubash and corruption – English Perceptions )

After the 1750s, the textile contracts which had provided the base of the power and authority of the Company merchants began to decline due to wars and political instability in the region. Correspondingly, the balance of social and economic power in Madras tilted towards the dubashes who appeared to have unlimited access to every aspect of English administration. Though the social landscape of Madras was being transformed, there was little changes in the way things were done. The more corrupt governors continued to extort money using the services of their dubashes. As the English in Madras were emerging as the major political power in the region, the governors could tap into one mor very lucrative source of money – the local rulers.

The saga of corruption continued till the end of the 18th century. In 1758. Robert Orme, the second in the Fort St.George Council was accused by governor Pigot of having demanded a ‘present from the Nawab of Arcot who had taken refuge in Madras at that time. Orme’s dubash Sunku Ram Chetti, ( one of the many members of the prominent family of Sunkuvar who had been living and trading in Madras since the beginning of the 18th century) was also accused of being involved in the extortion. Orme had demanded 20,000 pagodas from the Nawab, and his behavior has been so insulting to the Nawab in his durbar and within the hearing of even his sentry that the Nawab declared that he had decided that if ever Orme were to succeed to the governor’s office, it would be better for him to leave the province altogether and forgo the protection of the English. 8

It was also generally believed that the Nawab of Arcot had paid vast sums in 1776 to George Stration and members of the Fort St.George Council to overthrow governor Pigot, but this was never investigated formally. 9 In December 1781, an open inquiry was conducted under the orders of the Company about the bribes taken by Sir Thomas Rumbold, the dismissed governor, and several members of the Council. Rumbold had received money from the Raja of Tanjavur, the zamindars of the Northern Circars (northern Andhra region) and the Nawab of Arcot for various ‘favors’, especially for giving long leases on Company lands below their value. In 20 months in office he had received 6,50,000 pagodas, two and a half million rupees (together worth 5,60,000 pounds) and many valuable presents like diamond rings. In fact, it was believed that the amount of money was understated.10

The Nawab of Arcot refused to divulge any information during the inquiry, expressing his surprise that the Company would expect him to answer an inquiry which would prejudice his honor and dignity. The dubash of Rumbold, Vira Perumal, and three other dubashes were then summoned to give evidence, since they would certainly have known about their masters’ dealings. They refused to take the oath which they were asked to do, and declared that they were totally ignorant of the matters raised in the inquiry. As servants, they explained, if they were to be guilty of such a breach of confidence to their former masters, no one else would employ them. 11

One of the most spectacular cases of corruption occurred few years later, on a scale that was astounding even by the decadent standards of the Madras administration, and there was a full scale investigation in 1790 by a committee. The dismissed governor John Hollond, his brother Edward John Hollond and their dubash Avadhanam Paupiah were the subjects of the inquiry.12 Since this inquiry was held because of the charges made by the Nawab himself, full information was forthcoming from him. The corruption of the Hollonds and Paupiah was so pervasive that the committee extended the scope of its investigation and came to a definitive conclusion that bribes had been extorted from the Raja of Tanjavur and the Jagirdar of Arni, and, further, that money had been taken for the appointment of collectors. Though the report of the committee held that all three men were guilty of taking bribes, only the dubash Avadhanum Paupiah was actually tried and finally imprisoned. In all these three cases between 1750 to 1800 which had been formally investigated, there is little evidence that the dubash was more corrupt or guilty than his English master. In fact Sunku Rama Chetty and Vira Perumal had kept faith and behaved with greater integrity than the Englishmen who employed them. It is also worth noting that the actions of the Englishmen concerned were clearly against their own perceptions of what constituted a corrupt practice. Whereas in the Indian ethos, the use of public office and influence to grant favours in return for monetary consideration was quite common, and was perhaps not perceived as a misuse of official position. Yet it was only the Madras dubash who was publicly depicted as being totally corrupt, abusing the influence he had acquired through his employment and exploiting the position of his English master.

III ( ‘Baneful’ Influence of the Dubash )

The suspicion of dubashi power among the English, bordering on paranoia, had its basis both in objective reasons and in the English conception of the proper place that the local elite class should occupy in a well-ordered colonial social hierarchy. As the territory under the English grew in size and the administrative functions of the nascent colonial state expanded, so did the range and scope of dubashi activity which seemed to pervade all aspects of life in Madras. The fears of the English about dubashi influence became stronger as the administrative structure became more complex and the functions multiplied. Since the dubashes provided the necessary interface between the local people and the colonial government, the opportunities to misuse their position also increased exponentially. Among the English administrators hardly anybody knew the local languages, and few among the local population knew English. There are many references over the years in the proceedings of the Board of Revenue (BOR) to the misdeeds of the dubashes of collectors in several districts of the presidency, which gave enough reason to sympathies with the English perception that the dubashes were highly prone to corruption.

The English classed all employees from household servants to men of affaires under one common rubric – dubash – without making a distinction as to their relative status in society, their class background or the nature of their employment and regarded them all not merely as corrupt but also totally contemptible. By thus conflating several identities the English were able to create a composite identity which was an object of public ridicule and mockery.13 Susan Nield Basu sees in this attitude ” the latent ambivalences, frustrations and even fears inherent in the colonial situation.14 As Irschick observes, dubashes ‘ stood as a symbol of British bewilderment and powerlessness in the face of an apparently inscrutable local system. 15

The attitudes of the English towards the dubashes showed the same ambivalence and contradictions that could be seen in their public versus private attitudes towards the Company merchants in the early days of Madras. In spite of the public expressions of contempt and distrust, the private relations between the English and their dubashes was generally cordial and based on trust. Every governor relied heavily on his dubash and seemed convinced that his dubash was a trustworthy man of probity and integrity. In matters connected with the local institutions and usage – as for instance in the temple disputes – the dubashes were clearly making the decisions and articulating them through the Fort St.George Council to be announced as policy decisions. Dubashes were also rewarded by being appointed ‘dharmakartas’ of temples in Madras, to add to their social standing and reputation.

The concern of English administration in Madras over the pernicious influence of the dubashes turned into a public controversy after the Company decided to take the administration of Chengalpattu district into their own hands. The dubashes of Madras had gradually acquired influence in Chengalpattu district after the English received it as a jagir (Jaghire) from the Nawab. Lionel place, (who was collector of the district from 1794 to 1798) described in his report how the dubashes became so powerful in the district.16 The English had initially framed out the revenues to renters “of very low origin, needy and ignorant”, men who had no knowledge of revenue management. These renters were imposed upon by the ‘experienced artifice of inhabitants’ on questions regarding the share of the produce to be taken as land revenue. Mostly these men were the dependents of the dubashes of Madras, and the ‘instruments for effecting the iniquitous purposes of the latter’. Lionel Place believed that ‘ the influence of this diabolical race of men’ (that is, the dubashes) had not been so extensive when the district had earlier been under the management of the Nawab.

The dubashes had a considerable influence among Europeans because of their wealth even before the war of 1780, ‘ but it was not until the Company’s service received its subsequent improvements and multiplied their employment, that they grew into their present formidable numbers. “When the district was ravaged by war in 1780, many landowners had left their lands and fled to Madras. They had then sold lands to the dubashes in Madras. When peace returned and cultivation revived, the former landowners went back as tenants of the dubashes and in a condition of total dependence on the latter.

Place included “under this denomination of dubashes – almost any domestic, down to the lowest menial in the service European gentlemen” who had also acquired property in their home villages ” and by swelling their pretended importance, which an intercourse with Europeans gave them opportunities of doing, retained every inhabitant in subjection. ” The dubashes, Place commented, had gained in authority over the local people which was far more effectual that the authority of the government of Madras. They held durbars each day and decided all disputes, and no one could get a verdict in any English court which was contrary to the decision of dubash.

The confrontation between the dubashes and the Madras government came into the open when Company officials began to make revenue assessments in the district after 1783. A strategy adopted by dubashes to gain the loyalty of the inhabitants had been to accept all the claims of the latter about the shares of the crops between the cultivator and revenue officers, and the various customary claims on the produce by the agricultural laborers. The new revenue assessments by the English were naturally greatly resented, and there was a spirited resistance by the local inhabitants, led by the dubashes.17 The dubashes had wanted to acquire landed property to consolidate their social status, and not for augmenting their incomes. For the English, revenue collection was the first consideration, and thus the two objectives were naturally at variance.

Place was not alone in his opinion. It was generally believed that the extent of dubshi influencehad vitiated the Madras government and in 1792 the governor general, Lord Cornwallis, had written to the Court of Directors that he had no confidence that competent administrators could be found among the civil servants of Madras to take charge of the newly acquired Baramahal territory, since few knew the local language and both by habit and necessity had allowed all their affairs, official and private, to fall into hands of dubashes.18

Stung by such criticisms, Lord Hobart, who became the governor of Madras in 1794, became determined to bring down dubashi influence and appointed Lionel Place as collector of the Jaghir in 1794 to implement the new revenue assessments. Place had two main objectives – to restore cultivation and agriculture in the district and thereby augment its revenue potential, and to eliminate the influence of dubashes on both fronts, and the resistance to British reassessments which had earlier been confined to the Poonamalle area ( just south of Madras) spread to many other parts of the district.

The dubashes sent several petitions against Place and his high handed actions to the BOR, which often brought the board into conflict with the imperious collector. When the BOR asked Place for explanation, Place wrote that it was not possible for a collector “to stem the torrent of interest, intrigue and opposition” which the dubashes were capable of letting loose, unless the collector was “upheld by the strenuous and uniform support of superior authority”, a reply which aroused much resentment, especially in that it implied that the Board was acting under the influence of the dubashes.19 Place again wrote to the Board reasserting that the dubashes would emerge triumphant if the Board would not continue to maintain confidence in him, with a long complaint that his authority had been undermined by the BOR.20 The Board, for its part, protested to the governor, Lord Hobart, that they had indeed supported Place, but that Place wanted their “implicit and blind acquiescence in his will without investing or questioning his proceedings”, and the Board was not willing to grant this, it was ascribed to the ‘dubash facction’.21` This entire episode also made explicit the internal tensions and conflicts between the various tiers of the evolving colonial administration – the government of Madras, as represented by the governor and council, the board of revenue and the district collectors.

In the end Hobart resigned as governor and Place also tendered his resignation soon after. He wrote to the BOR that he had hoped that the new government under Lord Clive would have continued to support him, but that “the same baneful influence which opposed me at the outset in the Jaghire is on the watch and prepared to make another struggle to re-establish itself” , and that he had neither the courage nor the constitution to enable him to stem the torrent of intrigue and opposition.22 For its part, the BOR wrote that it desired to terminate Place’s appointment since he was ” so wholly void of prudence and discretion as to render it unsafe to have him in a situation where in those qualities are required.23 At least for the moment, it seemed that the dubashes had triumphed.

One of the major initiative suggested by Place to counteract the influence of dubashes was to restore the office of ‘nattavar’ (nattar) the traditional leaders of local communities, who, because of their status and knowledge of local conditions would be an effective and loyal ally of government in effecting the revenue settlement. Place thus constructed two contrasting identities – the loyal deserving nattavar as against the scheming and ungrateful dubash. The nattavar were the traditional leaders of society, and restoring them to their old rights would give them an interest and consequence in their district and ‘awaken’ an incitement to fidellity.24

The dubashes, on the other hand, lived in Madras and had other source of income. Their intervention in the rural areas had a bad effect on cultivation and they gave ” attention to their village property only as they required it to administer domestic conveniences”. To attach a numerous train of dependants gave a dubash a sense of self-importance. ” He teaches them to consider him their sanctuary in all difficulties, makes them his instruments in all plots and intrigues”, and thus had organized widespread opposition to the government.

One of the many Vellala dubashes whom Place named as the ringleaders of the opposition he was facing was Totttikalai Kesava Mudali. ‘This Man” wrote Place, “has acquired his immense fortune in the service of the Company, and in gratitude alone to that under which he has been raised from poverty and meanness to a condition of enormous wealth might by an example of ready acquiescence to have promoted the object in view.” Instead, there were “many instances of the interest of government being most injured and opposed by those who have been most cherished in the bosom of its protection”.

Place argued, with some-what perverse logic, that even if Kesava Mudali lost by the assessment which had been made, this would have mattered little to him, if one considered the vast amount of money that he spent on the annual festival of the temple of Tottikalai. After all, he had obtained the office of ‘dharmakarta’ “the most gratifying that a native can hold”, only because of his wealth, and this he owed to the English. And, finally, he urged that an example should be made of Kesava Mudali by depriving him of his prestigious office of dharmakarta.25

‘Loyal’ local leadership as constructed by Place and favoured by the English, had two qualities which were valued – humility and fidelity. This loyal class would provide leadership without dominance, in humble acknowledgement of the fact that they owed their position and privileges to a powerful and authoritative government. They would provide the interface between the colonial government and the masses, and also be the agency to make colonial rule acceptable to the people. He reaffirmed the general view that the English had of dubashes, that they were upstarts with no background who had gained their influence because of the wealth they had acquired which was only due to their service with the English, and yet had not behaved with proper gratitude. Place was also counterpoising the influence of dubashes on local society as evil and harmful, whereas a benign colonial government was acting in the interests of the people – in Irschick’s words, the “amoral” dubash and the “wise” British government.26

In this stand-off between the dubashes and Place, the former may have won in the short run. But in the long run, and in spite of the fact that they had the tacit support of the BOR, it was Place’s viewpoint which became the accepted official version of the dubash and his character. The Fifth Report of the Select Committee completely accepted Place’s account of the evils of dubashi influence.27

IV ( Dubash as Patron : Construction of Indigenous Identity )

In spite of the very public presence of dubashes as a collective group, their private and individual identities by and large remain locked in anonymity. Only a few dubashes are mentioned by name in the official records and it is difficult to recreate the antecedents and the multifarious enterprises of individual dubashes from the conventional records. A few, like Pachaiyappa Mudaliar of Kanchipuram, had a contemporary biographer. 28 For the rest we have to depend on less conventional sources, especially contemporary literature.

The 18th century saw a major social transformation in traditional rural society. Recurrent famines and wars devastated agriculture in many parts of the Tamil country, and impoverished the land owning upper classes. Most lesser kings and ruling families also lost their principalities in the shifting political alliances of the period. Patronage to poets and literature had essentially come from these classes, and their impoverishment left a vacuum in Tamil society. The emerging dominant men of affairs were the dubashes and merchants to whom the poets turned for patronage and monetary support. For the new rich in Madras and Pondicherry, patronizing poets, musicians and other artists provided the opening they desired which would put them on par with the traditional landowning elite who had been the accepted leaders and great men in society. The dubashes had gained power through their association with Europeans. But they also needed to be accepted as social leaders by their own people with a common, universally accepted reference point.

Most of Tamil poetry of the period was in the form of single verse ( known as ‘tanippadal’). Poets in search of patrons to support them with money and other gifts evidently travelled like itinerant bards composing short verses praising the various imaginary attributes of their potential patrons. Invoking the metaphors of classical poetry and deliberately resorting to the most flattering hyperbole, the poets constructed a new identity for the upcoming elite, recreating images and values from a heroic, classical past. In the process, the poets ignored completely the dependence that their patrons themselves had on the Europeans, and invested the dubashes with all the stature and authority of royalty. In this representation, sadly, they also missed the genuine achievements and entrepreneurial skills of the elite which had made it possible for them to survive in a changed environment.

Ananda Ranga Pillai was one such merchant and dubash, who was highly regarded as a generous patron of culture by poets. One poet described him as a person as learned as the thousand headed Adisesha. When even birds like parrots were repeating his name, who on this earth would not know him? 29 The same poet, Namasivaya Pulavar, also wrote a verse in honor of Ananda Ranga Pillai’s father, Tiruvenkata Pillai of Pondicherry.30 Another poet, Madurakavirayar, said that by approaching Ananda Raga Pillai of Pondicherry, who had shoulders like massive boulders, he had got to see the town and its tall mansions will gilded roofs, the smiling face of Annada Ranga himself, and got all the wealth that he wanted. 31

One other poetic metaphor used was to refer to these patrons as ‘kings’. Madurakavirayar refers to Ananda Raga Pillai as the protector of the world, the lord of men, who was exercising his sovereign authority over his domain extending through his conquest in all directions. Another poet described Ananda Ranga Pillai as the sovereign whose domain extended from Gingee to vijayapuram (for Vijayanagar?) and Delhi, who had conquered the countries of Vanga, Kalinga and Telenga (Bengal, Orissa and Andhra). 32

Ananda Ranga Pillai was probably the person most frequented by poets. In addition to short verses, several full length poetical works were composed about him which were presented to the public with much fanfare and ceremony. Ananda Ranga Pillai himself noted that an ‘ode’ in Telugu was composed about him by Kasturi Rangaiyan, a noted scholar of Trichi. This has been set to music and taught to dancing girls who had then performed it before the public at his friend’s house. 33 Another poem was the Ananda Rangan Kovai in Tamil, consisting of four hundred verses. This poem took sixteen years to be completed and when this was presented to Ananda Ranga Pillai in 1755, the author Tyagaraja Desikar was gifted with earrings set with gems, a necklace, pendant, shawl and land and money in Tiruvarur. 34 It is worth noting that by this date Ananda Ranga Pillai’s financial position had already become rather precarious, because of the problems he encountered in farming the revenues of the Carnatic and also a reflection of the general decline of Pondicherry.35 But the image of aristocratic behavior and grandeur had become so firmly ingrained in their own consciousness, that the habit of giving lavish gifts to poets and other clients had to be continued by the patrons whatever their real economic position.

A favorite theme of the poets was to recreate the genre of classic poetry like the ‘Ula’ in which the heroic king was glorified as the handsome, virile lover, who would be the object of passion of all women. It would be difficult to recognize the middle-aged merchants in this heroic garb, but the poets themselves went to great lengths to create this illusion. If the images were invoked through highly ingenious and contrived allegories and metaphors, it would get them a higher reward. The poet Madurakavirayar, having composed just such a complex verse describing the sexual prowess of his patron, presented it twice to two different persons.36 Another patron who was glorified as the great lover was Tottikalai (also referred to as Kalasai) Vedachala Mudaliar.37 In fact, the work Ananda Rangan Kovai referred to above, features Ananda Ranga Pillai as the (unlikely) romantic hero (‘talaivan’ in Tamil) and each of the four hundred verses mentions his name and extols his virility and greatness. 38

To elevate their patrons the poets often depicted themselves as totally dependent on these rich men. Savvadu Pulavar (perhaps Tamil for Javed?) said that men of letters looked to Ananda Ranga Pillai’s generosity for a gift as expectantly as the lotus looked to the sun, or peacocks to clouds to the rain.39 The poet Arunachalakavirayar, who had composed the Ramayana in Tamil in songs, refers to his patron, Manali MuthuKrishna Mudali ( the dubash of governor Pigot) also as a king (‘ bhupati’), learned in all languages and looked up to by everyone as a person who always spoke the truth. He also emphasized his dependence on Muddukrishna Mutali’s generosity by repeating the familiar images of dependence – lotus and the sun, crops and rain-giving clouds, a child and its mother.40

The degradation of abasing themselves and their creative skills by such sycophancy was not lost on the poets themselves. The poet Ramachandrakavi lamented that god had made his situation such that he had to beg for favors from everyone, humiliating himself. In another poem, filled with self – contempt, he says: I praised an ignorant man that he was learned, a man who had never known battle. I described as tiger, a man with narrow shoulders, I flattered that he had shoulders like a wrestler, and a miser, I hailed as a generous patron. As a just reward (punishment) for all my lies, he sent me away empty handed. 41

continued ………..